美国前国防部长盖茨:战胜中国的6大关键

编者按:罗伯特·盖茨曾在美国两党总统下出任高官,1991年到1993年为中央情报局局长,2006年到2011年为国防部长。他的专业是中国研究。本文2025年6月13日在《华尔街日报》发表,英文题目和题记是“The U.S. Can Rise to the Chinese Challenge–Since the end of the Cold War, America has let its nonmilitary instruments of power atrophy. Trump has a chance to revive them.”文章的中心意思是特朗普对联邦政府进行了重大改革,这正是重新安排有效的遏制中国战略的好时机。文章中文编译由NewTalk网站2025年7月27日发表。特转发该文供读者参考。编译文字略微粗糙,将该文英文贴在中文编译之后。

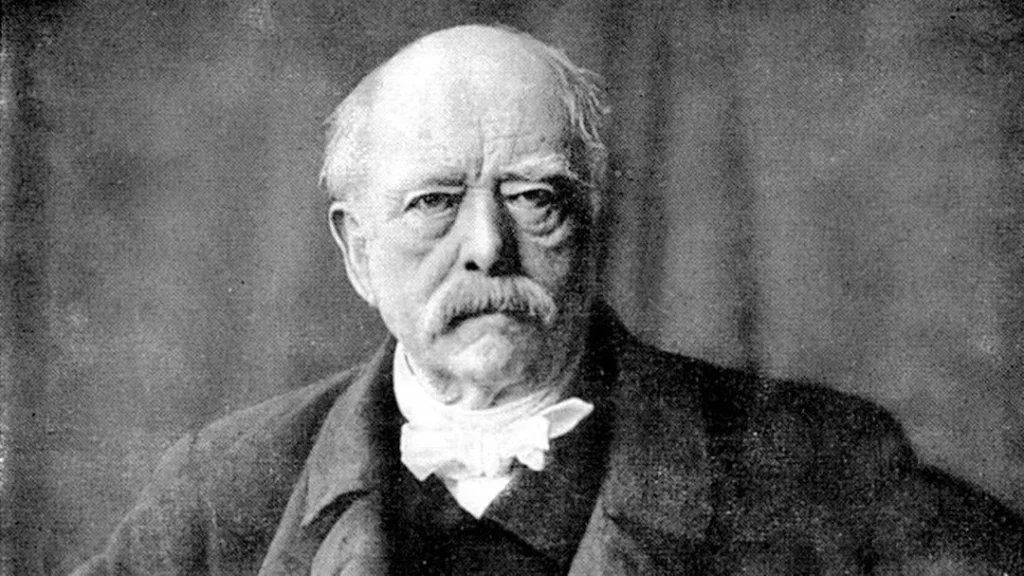

美国前国防部长罗伯特·盖茨(Robert Gates)曾任中情局(CIA)局长,并在共和与民主两党政府中担任国防部长,是一位受到跨党派尊敬的人物。 他在《华尔街日报》2025年6月13日的文章中表示:川普应该重建美国对抗中国所需要的非军事力量。

他指出,要勇敢面对与目前的中国之竞争,唯一的方法是倾听孙子所说的:“不战而屈人之兵,善之善者也。”美国当年在冷战中避免了与苏联的军事冲突,而很灵活地运用非军事的优势,并在最后取得了胜利。

这些优势包括:经济实力、技术优势、外交战略、铁幕内外的策略性宣传、发展援助与人道支持、安全保障的合作、同盟关系,以及意识形态的吸引力。 尽管苏联是军事上的超大强国,但在其他领域,尤其是经济与科技方面却是相对脆弱。 更幸运的是,从1950年代起,苏联的意识形态在全世界逐渐失去了它的吸引力。

但是,今天的中国是一个更为强大且多面向的敌人。 中国拥有广泛的贸易网络、网络攻击能力、尖端科技、灵活而且大规模对全球南方国家传播信息,以及“一带一路”与“数字丝路”等的倡议,成为比当年苏联更强劲的挑战者。

为了避免与中国发生战争,美国必须持续强化军事的吓阻能力。 但若要彻底胜出,光靠军事实力是不够的,非军事手段同样不可或缺。

过去这些负责非军事手段的政府机构是需要进行诸多的改革,并对各种课题加以整理,现在因为特朗普政府将这些机构加以解体,这反而为现在提供了一个重建的机会。 美国应该善用民间部门的优势,建立一个有效、精简而且具负责任的新制度。

目前中国在军事与科技上稳定扩张,其军工产能已经超越美国。 其庞大而发达的经济掌握了难以替代的供应链,例如稀土之,而具有能力要胁美国。 中国已成为超过120个国家(包含南美洲的所有国家)的最大贸易伙伴,它通过一带一路向约150个国家提供援助与建设计划,并在超过60个国家管理和运营超过100座的港口。

因此,重建美国非军事影响力的最佳方式,就是改革现有的政府机构并将之加以重构。 目前国务卿鲁比奥正朝这个方向在努力。

盖茨根据其自身经验提出了如下几项建议:

(1)在开发援助计划方面,应整并为“千禧挑战公司(MCC,Millennium Challenge Corporation)”与“美国国际开发金融公司(DFC,U.S. International Development Finance Corporation)”。

(2)战略性的国际传播应由国务院主导。 虽然编辑的独立性与诚实报道很重要,但这些媒体是政府的工具,必须遵循政策指导与国家安全上的优先事项。

(3)近年来对中国的出口管制措施是正确的。 为了阻止中国的军事扩张与技术进步,制裁与关税等其他经济手段也当然是合理的。 不过,对潜在的同盟国施加经济压力的作法应该要重新思考。 与这些国家合作,比起单方面的施压,更有助于推动中国经济政策的变更。

(4)美国在全球南方与中国竞争的过程中,外交和大使馆的存在至关重要。 关闭大使馆是一种错误,一定要任命正式的大使。

(5)应给予充足的预算。

(6)干涉他国的内政通常会产生反效果,在冷战时期,坚定支持自由、人权与个人尊严,提升了美国的国家利益与国际声誉。 同样的,在与中国的竞争中,意识形态依然是重要的关键。 “美国优先”主义,并不意味着放弃美国的核心价值。

特朗普政府动摇了许多过时的制度,这反而是一个强化美国非军事手段的绝佳机会。 如果错过了这个机会,反而会把战场拱手让给已渐渐要掌握主导权的中国。

最重要的是,由总统与国务卿跟国会合作,共同制定一套完整的国家整体战略,也就是如何在与中国的竞争当中,运用非军事影响力的综合战略。 现在已经没有时间可以再浪费了。

The U.S. Can Rise to the Chinese Challenge

Since the end of the Cold War, America has let its nonmilitary instruments of power atrophy. Trump has a chance to revive them.

By Robert M. Gates

June 13, 2025

The only way to rise to the Chinese challenge in the epic contest now under way is to heed the words of China’s great warrior philosopher, Sun Tzu: “The supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting.”

Because we were able to avoid a mutually catastrophic military conflict with the Soviet Union, we won the Cold War through the skillful use of nonmilitary advantages. These included economic power, technological superiority, diplomacy, strategic communications behind the Iron Curtain and around the world, development and humanitarian assistance, security assistance, alliances and ideology. We were lucky that the Soviet Union, while a military superpower, was weak in every other way, economically and technologically most of all. After the 1950s, its ideology had little appeal around the world.

America faces a much tougher, multidimensional adversary in China. Its extensive trade relationships, cyber prowess, advanced science and technology, skill and scale in communicating to the global south, and its Belt and Road Initiative and Digital Silk Road all make it a far more formidable adversary than the Soviet Union.

We must avoid a mutually disastrous shooting war with China by continuing to strengthen our military deterrence. But fully prevailing will require the diverse nonmilitary capabilities that were critical to winning the Cold War. President Trump inherited several institutions in this arena that were in serious need of reform, restructuring and refocusing. The administration dismantled them—creating the opportunity to rebuild our capabilities and make them far more effective for the battle. The challenge is to avoid the bureaucratic and programmatic flaws of past programs and create new ones that are effective, lean and accountable and that play to America’s strengths in the private sector.

This endeavor must start with a realistic view of the magnitude and danger of Chinese capabilities. Beijing is steadily growing more powerful and technologically advanced militarily, and its military industrial capacity now far outstrips America’s. China has a large, developed economy and the ability to hold the U.S. hostage in key supply-chain areas, such as refined rare-earth minerals, where we lack alternatives. It is the largest trading partner of more than 120 countries (including every country in South America), has development assistance and construction projects under the Belt and Road Initiative with some 150 countries, controls or manages 100 ports in more than 60 countries, and aggressively uses economic leverage to attain political and geostrategic objectives.

In the early 2000s, Xi Jinping’s predecessor, Hu Jintao, invested billions of dollars in a global communications network. Every country in the world receives Chinese radio, television, social media, print media and educational and professional exchange opportunities. All these media spread the message that the U.S. is in decline and China is the only reliable and predictable economic partner.

The Chinese are beating us at our own game. Since the end of the Cold War, the U.S. has let its nonmilitary instruments of power atrophy. In 1994, the allied committee to control the export of militarily sensitive technology was disbanded. In 1995, the House voted to abolish the U.S. Agency for International Development and in 1997 President Clinton agreed to consolidate the agency more fully into the State Department. In 1998, both Houses of Congress authorized the president to abolish the agency, but Mr. Clinton declined to do so. Also in 1998, Congress eliminated the U.S. Information Agency, the central element of our global strategic-communications network.

While elements of both USAID and USIA were transferred to the State Department, they were much reduced in size, resources and support. As other departments and agencies proliferated their own programs in development assistance, strategic communications and even international economic policy, the State Department was never given the authority to develop governmentwide strategies or to coordinate and oversee these nonmilitary instruments of power. All too often, the result was disjointed programs, mixed messages, waste, bureaucratic turf fighting and organizations like USAID and the Agency for Global Media (which took over Voice of America, Radio Free Europe and other USIA broadcasters) ignoring the secretary of state and even the president altogether.

After the Cold War, Republican and Democratic presidents lacked confidence in the traditional assistance agencies and created their own alternatives. Examples include Bill Clinton’s debt-relief initiative for Africa, George W. Bush’s Millennium Challenge Corp. and President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, Barack Obama’s Power Africa and Mr. Trump’s first-term Prosper Africa and the Development Finance Corp.

In the long term, the best way to reconstitute nonmilitary instruments of power isn’t to proliferate new, specialized organizations but to reform and restructure existing institutions, as Secretary of State Marco Rubio is trying to accomplish. Based on my experience, including as defense secretary, here is a starter set of suggestions for change:

Development-assistance programs should be consolidated and placed under the Millennium Challenge Corp. and the Development Finance Corp. When Mr. Bush proposed MCC in 2002, many conservatives argued it should replace USAID because of its requirements for accountability and insistence on recipient country buy-in. DFC is attractive because of its role in encouraging U.S. private-sector engagement. Both organizations should report to the secretary of state. Humanitarian assistance and international healthcare programs should be administered by the State Department, as Pepfar has been from its inception.

The State Department should also be in charge of all interagency strategic international communications programs to ensure consistency of message. Fourteen government departments and 48 agencies have strategic communications programs, yet there is no interagency coordination, much less a broad White House-approved strategy. The Agency for Global Media, with a budget of $700 million to run all U.S. government radio and other communications, over the years refused to take guidance from the president or secretary of state. Editorial independence and honest reporting are important, but these are instruments of the American government and must be responsive to policy guidance and national-security priorities. There also is a desperate need for innovation. The world has moved beyond getting news by radio.

Economic tools were essential to victory in the Cold War. The U.S. began limiting transfer of sensitive technologies to the Soviet Union in 1949. Recent presidents’ crackdown on exports to China was appropriate, if overdue. Other economic measures to impede China’s military buildup and technological progress, including sanctions and tariffs, make sense.

But if China is the main enemy, we need to rethink our use of economic sticks against potential allies. Some developed countries are as opposed as we are to many of China’s economic practices and policies. We’re much likelier to pressure China to change those policies by working in concert with other governments than by acting alone.

Diplomacy and an American presence on the ground matters in competing with China, especially in the Global South. Not only is it a mistake to close embassies there; we should make sure we have confirmed ambassadors representing us.

Without providing necessary money, restructuring all these instruments of power and better integrating them into U.S. national security-policy will be pointless.

We usually fail when we publicly nag other governments about their internal policies. Yet for most of our history, and especially during the Cold War, America’s national interest and reputation have been enhanced by consistent advocacy for liberty, human rights and individual dignity. America’s ideology matters in the contest with China. America First must not mean abandoning American values promoted by our government and by such organizations as the National Endowment for Democracy, the International Republican Institute and the National Democratic Institute. To neglect our values as part of our foreign policy would make us just another transactional great power without the unique appeal we have enjoyed for nearly 250 years.

The Trump administration’s disruption of outdated institutions provides a great opportunity to strengthen America’s nonmilitary arsenal. Failing to do so would mean abandoning the field to the Chinese, who already are running rings around us. Above all, there must be an overarching national strategy developed by the president and secretary of state—in collaboration with Congress—for applying nonmilitary instruments of power to the contest with China. We have no time to lose.

Mr. Gates served as director of central intelligence, 1991-93, and defense secretary, 2006-11.